Frank O’Hara and Elaine de Kooning with Reuben Nakian, 1966, photo George Cserna

The National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., is currently hosting a large exhibition devoted to the work of Elaine de Kooning. De Kooning, like her husband Willem, was a good friend and ally of many poets of the New York School.

The show, entitled “Elaine de Kooning: Portraits,” features de Kooning’s portaits of an interesting array of writers and artists, including familiar New York School names like Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery, Edwin Denby, Harold Rosenberg, Merce Cunningham, Fairfield Porter, and Alex Katz, along with Allen Ginsberg, Donald Barthelme, Ornette Coleman, and nine commissioned portraits of President John F. Kennedy.

The exhibition has been reviewed in the Washington Post (under the headline “Elaine De Kooning, Often Eclipsed by Her Famous Husband, Gets Her Due”), and now the website Hyperallergic has posted an excellent and thorough two-part review of the show by Tim Keane. In the first installment, Keane writes:

This massive exhibition —astutely organized by the museum’s chief curator, Brandon Brame Fortune … tracks Elaine de Kooning’s development as a first-rate, innovative portraitist through variously sized drawings, figure studies, trial sketches and small paintings across five decades, with each room dramatically highlighting the best of her large-scale oil paintings, some never exhibited publicly until now … the show offers uninitiated visitors a chance to discover an American artist who redirected techniques of twentieth-century vanguard painting into a form of portraiture that is as much about the rhythms and processes of human recognition as it is about the diverse characters who were her subjects.

Keane traces de Kooning’s “struggle to integrate abstraction into realistic portraiture,” which can be seen vividly in her famous portrait of Frank O’Hara:

Elaine de Kooning, “Frank O’Hara” (1962)

As de Kooning herself once explained about this painting:

When I painted Frank O’Hara, Frank was standing there. First I painted the whole structure of his face; then I wiped out the face, and when the face was gone, it was more Frank than when the face was there.

Of this portrait, Keane writes:

Like characterization in a novel, what she leaves out of the portraits becomes as important as what she puts in. The most famous example of this intentional game of hide-and-seek is, of course, her epochal “Frank O’Hara” (1962). During the late stages of its making, out of frustration, she erased the features of the poet’s face — believing, quite rightly, that once those facial details were replaced by just a fleshy pink smudge, O’Hara’s individuality would emerge more resoundingly from her depiction of the poet’s inimitable body language: the louche, lean frame; the pointy shoulders; the right hip pressing into his long, straight right arm; the fingers of his left hand barely hooked into the pocket of his beige chinos. Frenetic colors pass upwards and downwards around him, but rather than detract from the portrayal’s originality, the setting’s dynamism invites us to glide round and round the figure’s form, enriching our comprehension of the rendition.

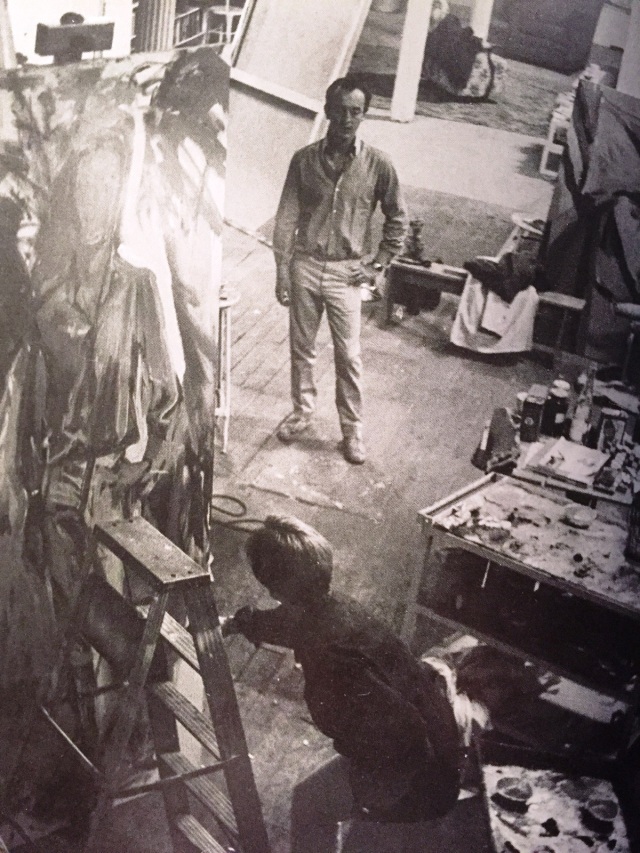

Tim Keane was kind enough to pass on this wonderful, little-known photo of O’Hara posing for this portrait in Elaine de Kooning’s studio:

from Elaine de Kooning, The Spirit of Abstract Expressionism: Selected Writings (1994). Photo by Eddie Johnson.

O’Hara, for his part, was nearly as fond of Elaine de Kooning as he was of her husband Willem, who was one of his most beloved heroes. In an essay looking back on the art world of the early 1950s, O’Hara referred to Elaine as “the White Goddess: she knew everything, told little of it though she talked a lot, and we all adored (and adore) her. She is graceful.”

In City Poet, his biography of O’Hara, Brad Gooch mentions that it was Elaine de Kooning who invited O’Hara to participate on a panel in 1952 on “The Image in Poetry and Painting” at the Club, the famous salon and meeting place for Abstract Expressionist painters. Gooch refers to Elaine as Frank’s “only peer in combining interests in writing and painting, talking and drinking, and in sharply appraising people.” Gooch also mentions that de Kooning was “described at the time as a female O’Hara for her plunges — often rescue missions — into other people’s lives.”

Keane also discusses how de Kooning had already used a similar “face-effacing technique” in a “massive” portrait of Fairfield Porter from 1954:

The broad-shouldered maestro of landscape and still life painting sits upright in a gray suit and red-and-blue striped tie. His large, masculine frame dwarfs the thin wooden chair so conspicuously that you can virtually feel that weight and bulk. His long legs are spread-eagled, his knees are bent at slightly divergent right angles, and his large hands dangle idiosyncratically near his inner thighs. It is portraiture as intimate panorama, a lustrously colored, high-octane composition coalescing from its pieces into a robust, patrician physicality that must have been quintessential Fairfield Porter.

Elaine de Kooning, “Fairfield Porter” (1954)

In the second installment of his review, Keane gives some interesting background on de Kooning’s experience painting JFK’s portrait (“how to humanize an overexposed, photogenic leader who had already been widely valorized and even self-mythologized”?) and assesses her renderings of the President (“her vivacious portraits of Kennedy,” he says, “seem like they were made last week.”).

Keane moves from JFK to little JA, discussing several portraits de Kooning made of John Ashbery:

A triptych of tondo portraits from 1983 featuring John Ashbery, created for a limited edition of prints to accompany a republication of the poet’s “Self Portrait in a Convex Mirror” (1975), replicate the shape of the circular mirror used by the Mannerist painter Parmigianino. Inspired by the optical distortions characterizing the Italian painter’s self-portrait, Ashbery’s masterpiece contemplates the compelling distortions and interactive nature of seeing and representation — what he calls, in the title poem, vision’s “recurring wave of arrival.” Elaine de Kooning’s renditions of Ashbery rely on lively semicircular lines and crosshatches that concentrically accentuate the poet’s wide eyes, prominent jawline and iconic mustache.

This exhibition, along with the recent attention bestowed on the work of Jane Freilicher, Joan Mitchell, Helen Frankenthaler, and Grace Hartigan (the subject of a new biography by Cathy Curtis), suggests that the great women painters of the New York School — who meant so much to the poets they befriended and painted — are having a welcome and overdue moment in the spotlight.

Frank O’Hara, Elaine de Kooning, Franz Kline (1957), photo by Arthur Swoger

Pingback: On Five Years of Locus Solus | Locus Solus: The New York School of Poets

Pingback: Grace Hartigan, Frank O’Hara, and the New York School | 1960s: Days of Rage