Yevgeny Yevtushenko, 1972

The great Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko died yesterday at the age of 83. A towering figure in post-World War II Russian poetry, Yevtushenko was, as the New York Times obituary put it, “an internationally acclaimed poet with the charisma of an actor and the instincts of a politician whose defiant verse inspired a generation of young Russians in their fight against Stalinism during the Cold War.”

But as a poet working within and against the Soviet state, Yevtushenko also had a complicated reputation and legacy:

He was the best known of a small group of rebel poets and writers who brought hope to a young generation with poetry that took on totalitarian leaders, ideological zealots and timid bureaucrats….But Mr. Yevtushenko did so working mostly within the system, taking care not to join the ranks of outright literary dissidents. By stopping short of the line between defiance and resistance, he enjoyed a measure of official approval that more daring dissidents came to resent.

While they were subjected to exile or labor camps, Mr. Yevtushenko was given state awards, his books were regularly published, and he was allowed to travel abroad, becoming an international literary superstar.

Some critics had doubts about his sincerity as a foe of tyranny. Some called him a sellout. A few enemies even suggested that he was merely posing as a protester to serve the security police or the Communist authorities. The exiled poet Joseph Brodsky once said of Mr. Yevtushenko, “He throws stones only in directions that are officially sanctioned and approved.”

This ambivalence towards Yevtushenko and his work may remind Frank O’Hara fans of his 1963 poem called “Answer to Voznesensky and Evtushenko.”

O’Hara’s withering poem attacks the pair of young Soviet poets as little more than pale shadows of the great Vladimir Mayakovsky and Boris Pasternak, two writers at the very top of O’Hara’s long list of personal heroes: “We are tired of your tiresome imitations of Mayakovsky,” the scathing poem begins.

Although O’Hara loves nothing more than Russian literature and culture (“we poets of America have loved you / your countrymen, our countrymen, our lives, your lives”), he seems to have had enough. O’Hara was particularly furious that Yevtushenko and Voznesensky had the gall to criticize American society on the basis of what O’Hara saw as ill-informed claims about American racism.

we are tired

of your dreary tourist ideas of our Negro selves

our selves are in far worse condition than the obviousness

of your color sense

….You shall not take my friends away from me

because they live in Harlem

(In defending America and its promise of diversity and interracial dialogue from these Russian interlopers, O’Hara’s poem notoriously traffics in some unfortunate racial stereotypes itself, but that’s a discussion for another day).

In O’Hara’s eyes, Voznesensky and Yevtushenko completely misunderstand race in America, while being lifeless imitators of the great Russian avant-garde:

you are indeed as cold as wax

as your progenitor was red, and how greatly was loved his redness

in the fullness of our own idiotic sun! what

“roaring universe” outshouts his violent triumphant sun!

you are not even speaking

in a whisper

Mayakovsky’s hat worn by a horse*

It’s worth noting that O’Hara’s anger at the young Russian poets may have been more a product of the complicated politics of race, nationalism, and Cold War allegiances in 1963, than a blanket dismissal of Yevtushenko and his writing.

In later years, he may have felt quite differently — it seems that O’Hara’s friend Kenneth Koch did. Yevtushenko’s death immediately reminded me of an event in 1996, when Kenneth Koch invited Yevtushenko to read at Columbia University as part of the F. W. Dupee Reading series. At the time, I was helping Koch run this series, so I happened to be involved in coordinating and advertising Yevtushenko’s reading. I recall Koch’s enthusiasm leading up to the visit, and remember the rousing introduction he gave the Russian poet. Yevthushenko proceeded to give a vibrant performance of his poems, dramatically gesticulating and stalking the stage as he read in a booming voice. I remember Koch’s being half-bemused and half-inspired by Yevtushenko’s thundering performance and also being shocked that I (a young grad student kid) was invited to a little champagne reception afterwards with these two poets and other VIPs …

I hadn’t thought about this event in a long time, but digging around, I just found a brief article about the reading in the Columbia Spectator. The Spectator reports that in his introduction, Koch said Yevtushenko “seems indifferent to nothing and responsive to everything … His poems of private feelings are as radical as the others.” The article goes on to describe the reading: “Yevtushenko presented, in English and Russian, both prose and poetry, often making large gestures with his arms and whole body and wandering across, and off, the stage as he read and recited his work.”

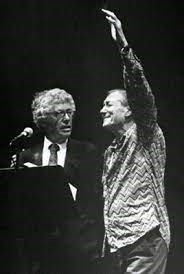

Here is a picture of the two late poets, Koch and Yevtushenko, on that night in 1996.

*As usual, the spacing of these lines is all off because Word Press makes it impossible to reproduce poetry that has any indentations or unusual spacing. My apologies. You can find the poem here, in O’Hara’s Collected Poems.

Pingback: The red mascarade | housewithoutdoors

Pingback: Another Night at Columbia: Allen Ginsberg in 1995, Standing Room Only | Locus Solus: The New York School of Poets